Updated February 22, 2025

This article covers the basics of coastal foraging in Northern California. However, most of this information will also help you forage anywhere on the West Coast (Baja to Alaska). Coastal foraging is a fun and sustainable way to gather fresh seafood without costly barriers to entry seen with traditional fishing. No boat or fancy equipment required. Due to its accessibility, coastal foraging makes for an excellent group activity with family or friends. With just a bit of knowledge from this article, you'll be ready to head out to your local beach and do some foraging of your own.

So what exactly is "Coastal Foraging"?

Coastal Foraging, also known as Tidal Foraging, is the practice of gathering wild, edible marine life—such as shellfish, crustaceans, seaweed, and other intertidal species—specifically during low tides. Tides in Northern California typically range between -2 feet to +6 feet. For coastal foraging, we look for low tides less than 0 feet; this is because, as the ocean recedes, it reveals rocky outcroppings, tide pools, and sandy flats teeming with life that would otherwise be hidden and/or not accessible.

The goal here is to get you ready to plan a session of your own. This article will help answer the following questions:

- What rules and regulations do I need to know about before I go?

- What marine life might I find while foraging?

- Can I eat everything I catch?

- What equipment can/should I use?

- Where should I go coastal Foraging?

- When should I go coastal foraging?

- What is Poke Poling?

Rules and Regulations

Before we get into the fun stuff, it's essential to understand that every person, 16 years or older, must have a valid fishing license while foraging. Luckily, it's simple, and you can purchase an annual, one-day, or two-day license online. Although online seems easier, the website is not great and could cause unnecessary questions and confusion – to avoid all doubt, we suggest walking in and purchasing your license at your local Walmart or sporting goods store. It will take 3 minutes, and you'll leave with peace of mind knowing you purchased the right license.

Other than a License, before you go out foraging, it's important to understand the following:

- Bag limits - restricts the number of a certain species you can collect in a single day. These limits help prevent overharvesting and maintain healthy populations. You can find the latest information here.

- Size Limits - Some species have minimum size limits. This helps protect juvenile populations and allows individuals to reproduce before being harvested. You can find the latest information here.

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) - locations that restrict or prohibit foraging and fishing to protect marine life. You can find the latest information here.

- Health Advisories - Toxic algal blooms (red tide) and water quality concerns can close harvesting of certain species. You can find the latest information here.

This article will provide more detail on each of these points, so read on.

What Can You Find While Coastal Foraging?

One of the most exciting parts of coastal foraging is the variety of marine life you can discover. Northern California's intertidal zone is home to an abundance of edible species, from clams hiding beneath the sand to prized purple urchin clinging to rocky surfaces, to the nutrient-rich seaweed draping the tidal floors. Below are some of the most foraged specimens along the Northern California coast:

Shellfish

Bivalves like mussels, clams, and oysters can accumulate harmful toxins, especially during harmful algae blooms (red tides). These toxins, such as domoic acid and paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP), cannot be removed by cooking and can cause serious illness.

Before harvesting any bivalves, always check for health advisories from the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) or local agencies. Conditions can change often, so please call the biotoxin hotline at 1-800-553-4133 before any trip. For ease of use and as a supplement to the hotline, You can also find the latest information on FishNotify's coastal foraging forecast page: https://fishnotify.com/coastal-foraging

Mussels

Found attached to rock clusters at pretty much any beach along the West Coast, these are one of the easiest and most abundant shellfish to collect and, therefore, are an excellent first target for beginners

- Edibility: On the California coast, you'll run into two different species, the California Mussel and the Bay Mussel. Although both are edible, you should prioritize California Mussels. The Bay Mussel, as its name suggests, is found in bays, and as a general rule of thumb, especially for those new to foraging, It's best to avoid bays, primarily due to pollution and water quality issues. Like most bivalves, mussels can accumulate toxins, so always check local advisories before harvesting.

- Know before you go: You must harvest mussels by hand. You can not use tools to separate the mussel from the rock (mussel bed). So be sure to bring gloves to help you grip and twist mussels from the rock. You can harvest up to 10lbs of mussels per day, including the shell. There is no size limit.

Clams

Buried in sandy or muddy flats, clams require digging and can be challenging to locate but are well worth the effort.

- Edibility: Along the Northern California coast, common edible species include Littleneck, Cockles, Gaper, Butter, and Razor Clams. While all are safe to eat, Clams can be gritty and sandy, so be sure to "purge" your clams before consuming. To purge, simply submerge your clams in a bucket of cold salt water for a few hours. Like all bivalves, clams are filter feeders, so soaking them in salt water allows them to filter out sand or grit.

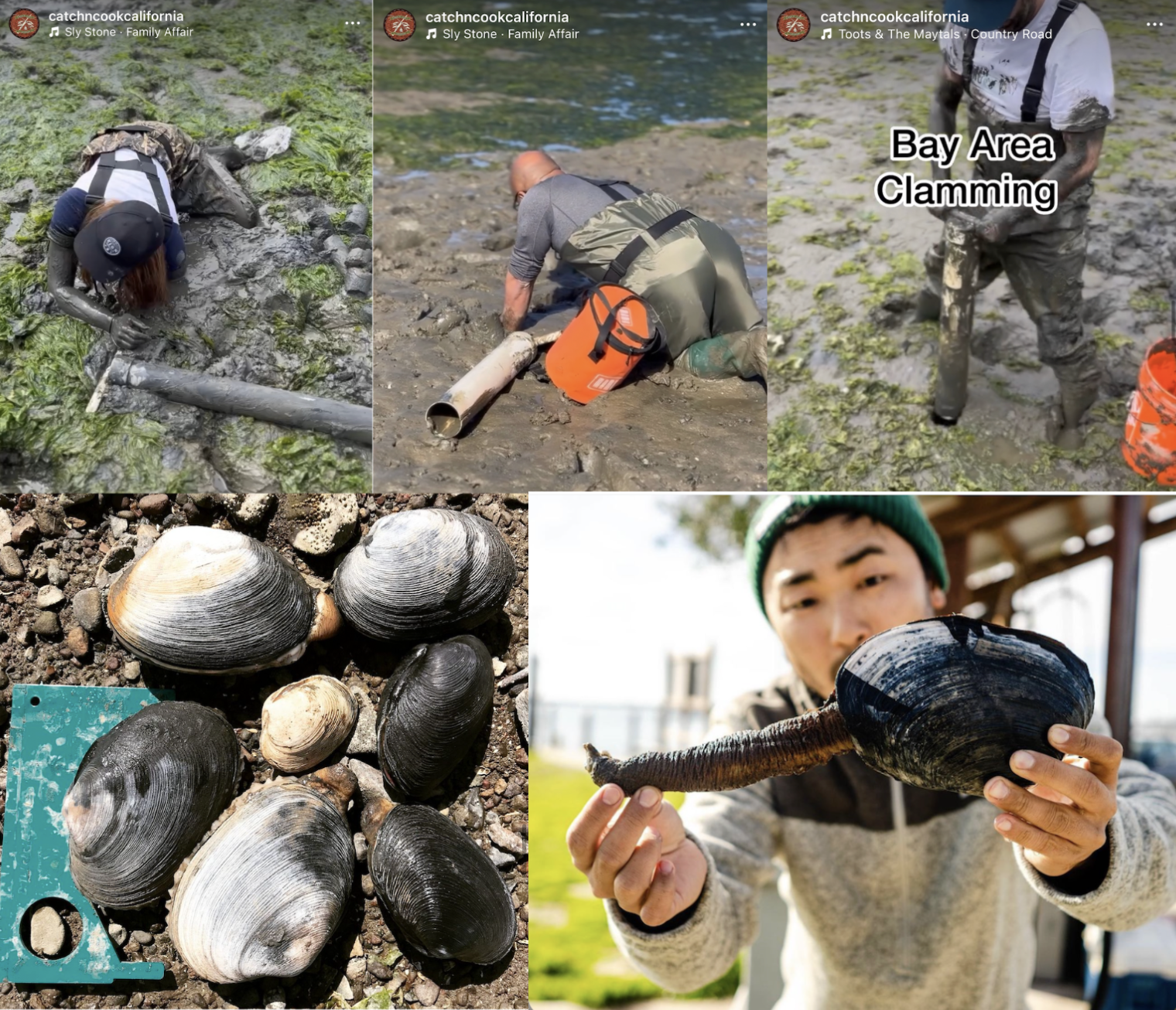

- Know before you go: Clams closer to the surface, like littleneck clams and cockles, can be dug by hand or with a small rake, but most other species tend to burrow deeper, which will require a shovel or clam gun to reach. Each species has different size and bag limits, and all clams must be kept in their shells until you reach home. Because technique, location, and regulations vary across the clam species, we plan to create a clam-specific How-to Guide. But if you're keen to hit the sand now, We'd recommend taking a local foraging class with one of the local guides, such as CatchNCookCalifornia or Seaforager.

Oysters

Found in rocky intertidal zones, estuaries, and bays. Unfortunately, outside of a few bays and commercial farms, this bivalve is not a common occurrence in northern California.

- Edibility: If you are fortunate enough to find a wild population of Pacific Oysters, they are safe to eat raw or cooked. Like clams and other bivalves, oysters accumulate pollutants, so be mindful of local water quality reports before harvesting.

- Know before you go: Like mussels, you must harvest oysters by hand—prying them off rocks with tools is prohibited. There is no size limit. Bag limit is 35 oysters per day per person.

Rock Crabs

These aggressive crabs are plentiful on the Northern California coast. Wherever there are rocks/boulders, you'll find rock crabs lurking in crevices and under ledges.

- Edibility: Very edible! There are three types of Rock crabs: Red, Yellow, and Brown; all three have firm, sweet meat, especially in the claws. Highly underrated because their bodies contain less meat than their more popular cousin, the Dungeness crab (not often found in tide pools)

- Know before you go: You can only harvest rock crabs by hand or with a crab snare—no traps allowed in intertidal zones. Spearfishing, hooked devices, and dip nets are also not allowed. Due to their abundance, the daily bag limit is 35 rock crabs per person. The minimum size limit is 4 inches measured across the shell, also known as a carapace (see illustration below). Although you can harvest males or females, foragers tend to release females so they can reproduce. Lastly, the rock crab season is open year-round, so these make for a tasty and reliable target.

Shore Crabs

Small, hardy crabs commonly found in tide pools, and rocky intertidal zones. They are one of the easiest crabs to find along the California coast.

- Edibility: While technically edible, foragers rarely harvest shore crabs for food due to their small size and minimal meat. However, these crabs make excellent bait for larger fish like rockfish, lingcod, and cabezon.

- Know before you go: Shore crabs are best collected by hand and there are no specific size or bag limits. The only note is that if/when you flip rocks, always return the rocks to their original position to avoid disturbing marine habitats.

Other Common Intertidal Species

Sea Urchin

Found near kelp forests and rocky intertidal zones, sea urchins are spiny, slow-moving echinoderms that graze on algae like kelp and seaweed

- Edibility: Highly prized for their roe ("uni"), sea urchins have a creamy, briny flavor and are a delicacy in sushi and seafood dishes. The Red Sea Urchin is the larger and more commonly harvested species for table fare, while Purple Sea Urchins are smaller but more plentiful and can be equally delicious.

- Know before you go: Due to the decline in natural predators like sea stars and sea otters, Purple Urchin's population growth has become unsustainable in northern California and has ultimately led to the destruction of our kelp forests. Because of this dynamic, there is no harvest limit on purple urchin. That said, we don't have the same problems with red urchins, and there is a daily bag limit of 35 per day per person. Unlike alot of the other species mentioned above, you can use a small knife or tools to pry urchins from rocks. Go get them!

Abalone

Once abundant along the California coast, usually clinging to submerged rocks and boulders, abalone populations have dramatically declined due to overharvesting, poaching, and environmental changes.

- Edibility: Highly prized for its tender, flavorful meat, abalone was a staple seafood in California.

Important Abalone Notice

All recreational and commercial harvesting of wild abalone is currently prohibited and illegal in California.

Snails

Common in rocky intertidal areas, these marine snails are slow-moving and attach themselves rocky surfaces

- Edibility: Most species, such as California Whelks, Periwinkles, and Turban Snails, are edible and commonly used in seafood dishes worldwide. However, some species, like dog whelks, are unpalatable. Like bivalves, snails can accumulate toxins, so always check local advisories before harvesting.

- Know before you go: Snails can be collected by hand. No tools are necessary. Most species have a bag limit of 35 snails per day per person. There is no size limit.

Octopus

More common in Southern California, though still present toward the north, these highly intelligent creatures can be found crawling in rocky intertidal zones and tide pools

- Edibility: There are two core species of Octopus in the California intertidal zone. Both of which are edible and highly regarded. You are more likely to run into the Two-Spotted Octopus in the south and the Pacific Red Octopus in the north

- Know before you go: There is a bag limit of 35 per day, but there is no size limit for recreational collection in California. Foragers can harvest Octopus by hook and line or hand year-round.

Edible Seaweed & Kelp

Tide pools hold something for everyone, even when meat isn't your thing. Found attached to rocks, floating in tide pools, or washed ashore after storms, edible algae and kelp can be found all along the California coastline.

- Edibility: These Sea Vegetables are an excellent source of iodine, fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants. Technically, all seaweed and kelp are edible, but most are forgettable. As such, we compiled a list of the most commonly harvested algae below:

- Nori: Thin, paper-like red algae used in sushi, soups, and snacks. It has a mild, slightly sweet ocean flavor.

- Wakame: A tender brown algae commonly found in miso soup and salads. It's slightly sweet and has a soft texture when rehydrated.

- Sea Lettuce: A bright green, leafy seaweed with a mild, slightly peppery taste, perfect for raw salads or soups.

- Kombu: A thick, umami-rich kelp used to make dashi broth and enhance flavors in various dishes.

- Kelp (Giant Kelp & Bull Kelp): A versatile seaweed becoming increasingly common. The stipes (stems) and blades (leaves) are both edible, with younger, tender parts being the most desirable.

- Know before you go: Avoid collecting near harbors, marinas, or polluted waters, as seaweed absorbs contaminants from its environment. To harvest sustainably, bring a knife or scissors and only cut what you need, allowing it to regenerate. Never harvest by pulling it from the base. Individuals are allowed to harvest up to 10 pounds of marine algae per day in total. You can not harvest Eelgrass, Surfgrass, or Sea Palm in Northern California.

Where Should I Go Coastal Foraging?

While you'll definitely have fun exploring any beach during low tide, choosing an optimal spot for coastal foraging requires you to consider habitat type, MPAs, and health advisories.

Habitat Type

- Rocky Shores & Tide Pools – Ideal for most intertidal species like mussels, barnacles, limpets, seaweed, urchins, and crabs.

- Sandy & Muddy Flats – The best places to dig for clams and other burrowing creatures like ghost shrimp and sand fleas

- Jetties & Breakwaters – These structures attract rock crabs, snails, and fish that can be caught using poke poles.

Regulations

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are designated sections of the coastline where fishing, foraging, and other extractive activities are restricted or entirely prohibited. You can explore all MPAs here.

There are 2 main MPAs that foragers need to be aware of:

- State Marine Reserves (SMRs) prohibit all forms of take, meaning you cannot fish, forage, or remove any marine life (including seaweed and invertebrates).

- State Marine Conservation Areas (SMCAs) – allow limited harvesting, meaning you can take certain species but with strict regulations on how much, how, and what species

It's better to be cautious, and we recommend that first-time foragers avoid SMRs and SMCAs altogether.

Other than SMRs and SMCAs, you might run into the other 2 types of MPAs: SMPs and SMRAs. These 2 seldom restrict recreational fishing activities; therefore, you shouldn't have to worry about them as much when foraging. If curious, see the descriptions below:

- State Marine Parks (SMPs) – allow recreational fishing and foraging but ban commercial fishing activities. These areas are designed to provide opportunities for sport fishing and recreational foraging while preventing large-scale commercial extraction.

- State Marine Recreational Management Areas (SMRMAs) – are special zones that balance recreation and conservation. They often exist near estuaries, wetlands, or lagoons where marine life is particularly sensitive. In some SMRMAs, fishing is restricted seasonally or limited to certain gear types.

Health Advisories

Even outside of MPAs, temporary closures may be in effect due to:

- Toxic algal blooms (red tide) and water quality concerns.

Always remember to call the biotoxin hotline at 1-800-553-4133 before any trip. For ease of use and as a supplement to the hotline, You can also find the latest information on FishNotify's coastal foraging forecast page: https://fishnotify.com/coastal-foraging

When Should I Go Coastal Foraging?

Timing is everything when it comes to coastal foraging. The ocean's tides will dictate when intertidal zones become accessible, meaning there are times of day and year when foraging is impossible, at least not without diving gear. As stated earlier in this article, foragers should look for negative tides. But please remember that this is a general rule of thumb and can vary based on the beach and target species. Fortunately, there are dozens of tide forecasting websites to help you understand daily tide movement (Our favorite is Fishnotify ;))

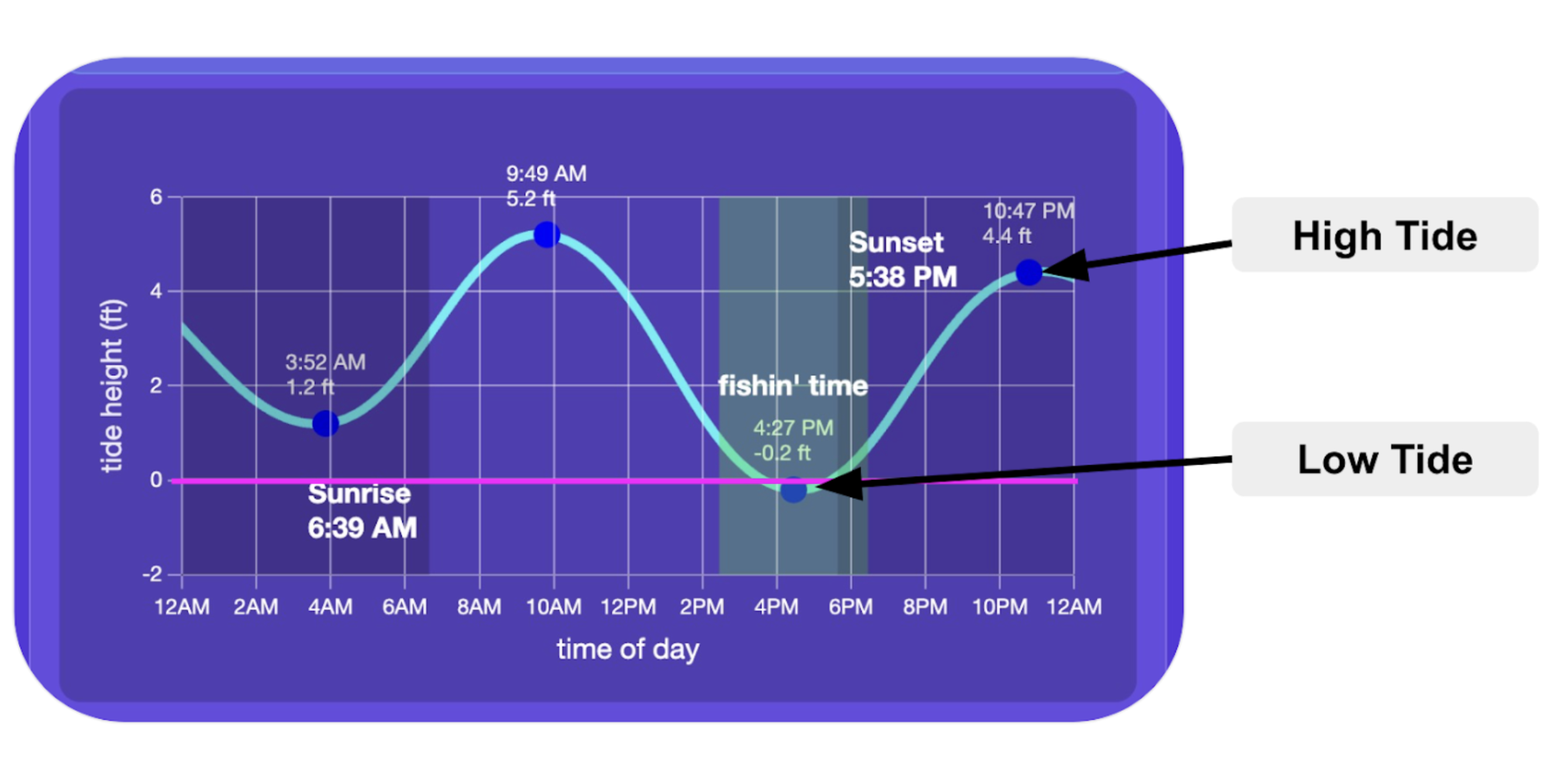

Tide forecasting sites will usually have an illustration like the one below:

Ideally, you're looking for the low tide to drop below zero (the pink line). The tides in the above chart aren't the best for foraging, but they aren't the worst. We'd suggest looking for a different day if possible, but if you have to go on this day, you should go between 2pm and 6pm. This is when the tide is lowest and even turns negative briefly.

Most new foragers will do just fine by understanding tide optimization. Still, there are several other factors that seasoned foragers consider when determining whether the day is good or not for foraging. These include but are not limited to the following:

- Delta between the high and low tide

- Season

- Weather

- Swell height

- Swell period

Knowing when to forage will help maximize your chances of a safe and successful trip, and as mentioned earlier, understanding tides will get you 80% of the way there. The good news is there are a lot of trustworthy websites to help you with this. The bad news is that many websites can be overly complex and clunky. For this reason, Fishnotify built a coastal foraging feature.

As a user looking for the best time and day to forage, you simply enter your desired beach; Fishnotify will then evaluate the day on a scale from 0-100, with 0 being terrible and 100 being the best foraging day ever. You can also see foraging scores and conditions for the rest of the week and set alerts to get notified when a good day is coming up at your favorite foraging beach. Give it a try, and let us know what you think.

Poke-Poling

The previous section covered most of the species you can encounter while walking around in the intertidal zone. If you finished that section feeling like it was missing something, you are not alone, and it is probably due to the lack of fish. As it turns out, the exact conditions that make coastal foraging possible are the same conditions that make for seemingly terrible fish habitats – little to no water.

Although that statement usually holds true, there is a large and fun caveat. As the tide recedes back into the ocean, it exposes large rocks and holes that previously housed fish when they were a few feet underwater. Fortunately for foragers, fish sometimes get stuck in these holes and are forced to wait for the next high tide before they can escape. Enter poke poling, a traditional, low-cost, and effective method of fishing that involves "poking" a long pole in between these rocks, hopping to trigger the bite of an unsuspecting fish.

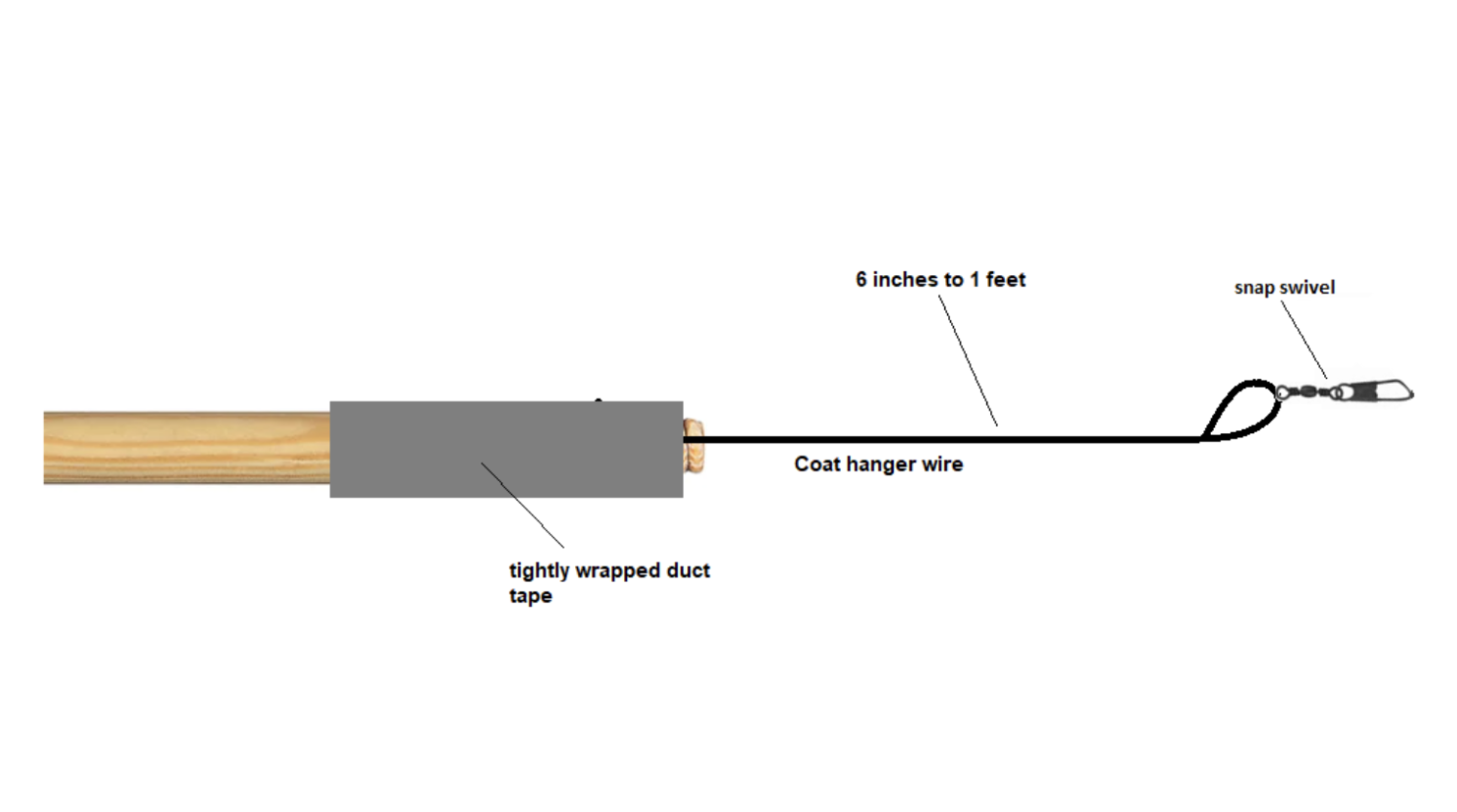

To make a poke pole, you need the following:

- Long rod-shaped stick, often bamboo or PVC

- Coat hanger, which attaches to the top of the stick

- Fishing line and hook which attach to the coat hanger or swivel

The coat hanger will help you insert your pole into harder-to-reach crevices. You can use anything as bait, but squid is often preferred because it has a strong scent and is difficult for a fish to rip off the hook. You'd be surprised by the size of fish you can pull out of these holes, with the most common being rockfish and the monkeyface prickleback eel (not a real eel). Although less common, catching cabezon, kelp greenling, lingcod, and crab is possible. Any crab caught using this method must be released.